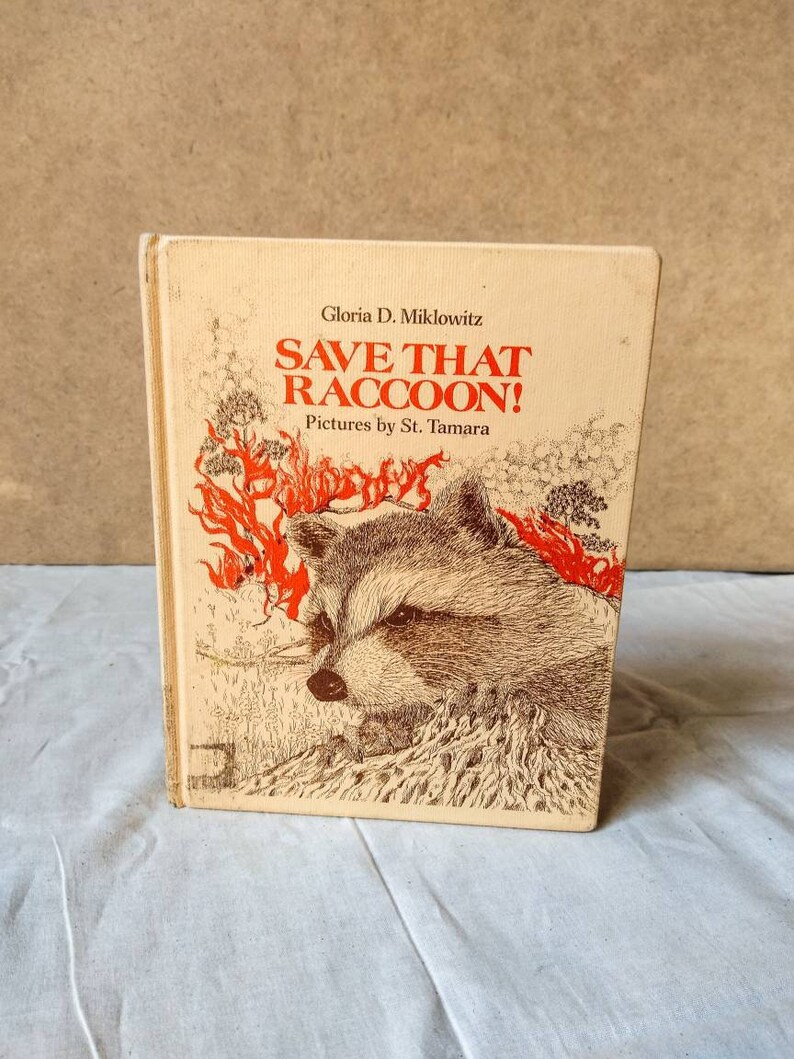

Emiko Sumoto-always “Amy” at school-is a middle-class Japanese-American girl whose boyfriend, Adam, is a rich white bro. That romance crosses both color and Color Game lines. Her prose in The War Between the Classes is workaday, her dialogue often preachy characterization is quick and simple, and the obligatory YA romance is useful to the plot, but predictable. Miklowitz specialized in YA novels about social issues: cult recruiting, nuclear war, teen suicide, single motherhood. The Wave has two fairly simple messages: “The desire to belong will dull your conscience,” and, “Anybody will buy into fascism if you market it right.” The War Between the Classes is teaching subtler lessons about shame, solidarity, and meritocracy.

But as an exercise for college students, led by an experienced teacher, the Color Game proved popular-and Miklowitz’s fictional version offers far more insightful social criticism than the usual YA “the game got out of hand!” cautionary tale. Otero was sued in 1988 by the parents of a high school student who claimed her experience as a “lower-class” Color Game participant had traumatized her. And the real-life game didn’t please everybody, especially once it moved beyond the control of its developer. The story of the Third Wave has had a recent renaissance in Germany, with a 2008 film and a 2019 Netflix series, We Are the Wave.Īlthough Miklowitz’s novel did get a 1985 Emmy-winning television adaptation, the Color Game never managed the big pop culture footprint of the Third Wave. The Third Wave has inspired everything from a Canadian musical to an episode of the children’s cartoon “Arthur”-and even a Sweet Valley Twins book, 1995’s It Can’t Happen Here. The experiment got out of hand, of course, leading to both a fictionalized TV movie and a novelization, The Wave, in 1981. Perhaps the experiment that had the greatest impact on ’80s pop culture was “The Third Wave,” a 1967 exercise intended to teach California high school students about the rise of Nazism. (You can watch a short 1983 feature on the Color Game here.)

Otero’s “Color Game,” in which students wear armbands whose colors indicate whether they’re upper-class, upper-middle, lower-middle, or lower, is one of many similar classroom experiments in which students take on new identities in the hopes of gaining insight into social dynamics. But it’s also the premise of a real classroom exercise developed in the late ’70s by Occidental College Professor Ray Otero. Miklowitz’s 1985 young adult novel, The War Between the Classes. Make sure the artificial hierarchy affects the students’ friendships and grades. Give other students the power to enforce class boundaries and punish those who get ideas above their station. Assign teenagers to different socioeconomic classes and require the lower classes to perform humiliating rituals of obeisance to the upper.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)